Bridget O'Donnell

You may not recognise the name Bridget O’Donnell, but she is one of the most recognisable women in Irish history.

In December 1849 her image (Re-presented in the artwork and here) appeared in The Illustrated London News. Over the following decades she became the face of the Great Famine.

A symbol of resilience amidst the Great Famine, she endured unspeakable hardships. Born in County Clare, Ireland, she faced the horrors of starvation, eviction, and the loss of her husband and four children.

Today she is one of the most recognisable women in Irish history, but who was Bridget O’Donnell?

Please read on below to find out.

The following appeared in The Illustrated London News, 1849-50: Issue of December 22, 1849

The Famine in Clare: Condition of Ireland - Illustrations of the New Poor-Law.

The Sketch of a Woman and Children represents Bridget O’Donnell. Her story is briefly this:- “I lived,” she said, “on the lands of Gurranenatuoha [Garraunnatooha, Kilmacduane Parish]. My husband held four acres and a half of land, and three acres of bog land; our yearly rent was £7 4s.; we were put out last November; he owed some rent. We got thirty stone of oats from Mr. Marcus Keane, for seed. My husband gave some writing for it: he was paid for it. He paid ten shillings for reaping the corn. As soon as it was stacked, one “Blake” on the farm, who was put to watch it, took it away in to his own haggard and kept it there for a fortnight by Dan Sheedey’s orders. They then thrashed it in Frank Lallis’s barn. I was at this time lying in fever. Dan Sheedey and five or six men came to tumble my house; they wanted me to give possession. I said that I would not; I had fever, and was within two months of my down-lying (confinement); they commenced knocking down the house, and had half of it knocked down when two neighbours, women, Nell Spellesley and Kate How, carried me out. I had the priest and doctor to attend me shortly after. Father Meehan anointed me. I was carried into a cabin, and lay there for eight days, when I had the creature (the child) born dead. I lay for three weeks after that. The whole of my family got the fever, and one boy thirteen years old died with want and with hunger while we were lying sick. Dan Sheedey and Blake took the corn into Kilrush, and sold it. I don’t know what they got for it. I had not a bit for my children to eat when they took if from me.”

Her poignant testimony, recorded in "The Lament for Ireland" by Michael J. McCann, echoes the anguish of countless Irish families during the mid-19th century famine. O'Donnell's story embodies the collective suffering and strength of a nation devastated by famine, evoking empathy and shedding light on a dark chapter in history.

However, the Great Famine, its consequential decimation of Ireland’s population and ongoing scarring of the Irish psyche, was far more than a potato blight. In Irish it is called, An Gorta Mór: the Great Hunger

The Great Hunger in Ireland led to the greatest loss of life in western Europe in the 100 years between the Napoleonic Wars and World War I.

To read more about the prelude and reasons for this preventable catastrophe and it’s after effects please read further here

An account of the effect of An Gorta Mór as experienced in Manchester is provided in an excellent publication.

The Great Hunger in Manchester by Michael Sheehan

Between 1845 and 1852 over one million people left Ireland to escape the horrors of the Great Hunger. Sadly, for many of the Irish Famine refugees who arrived in Britain, the nightmare of starvation, disease and death continued.

The Great Hunger in Manchester highlights the stories of some of the families who came to Manchester and the surrounding areas during the Famine.

An extract can be found here

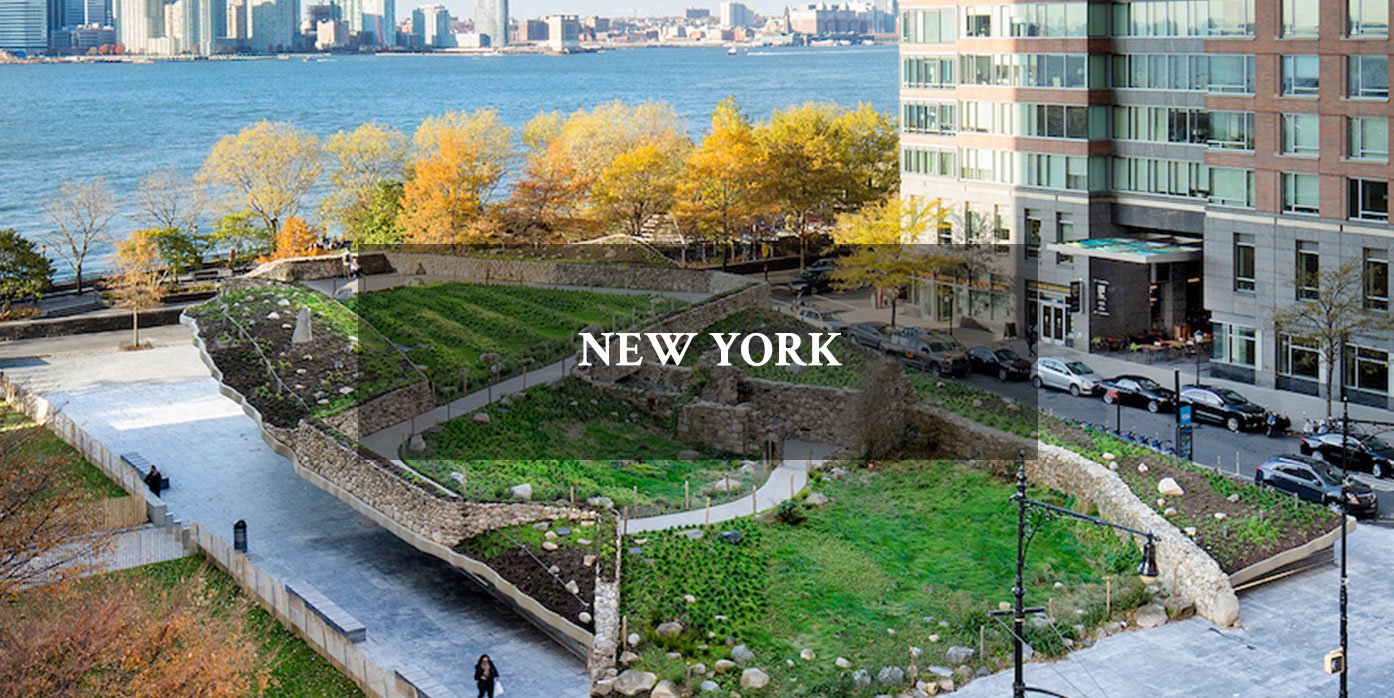

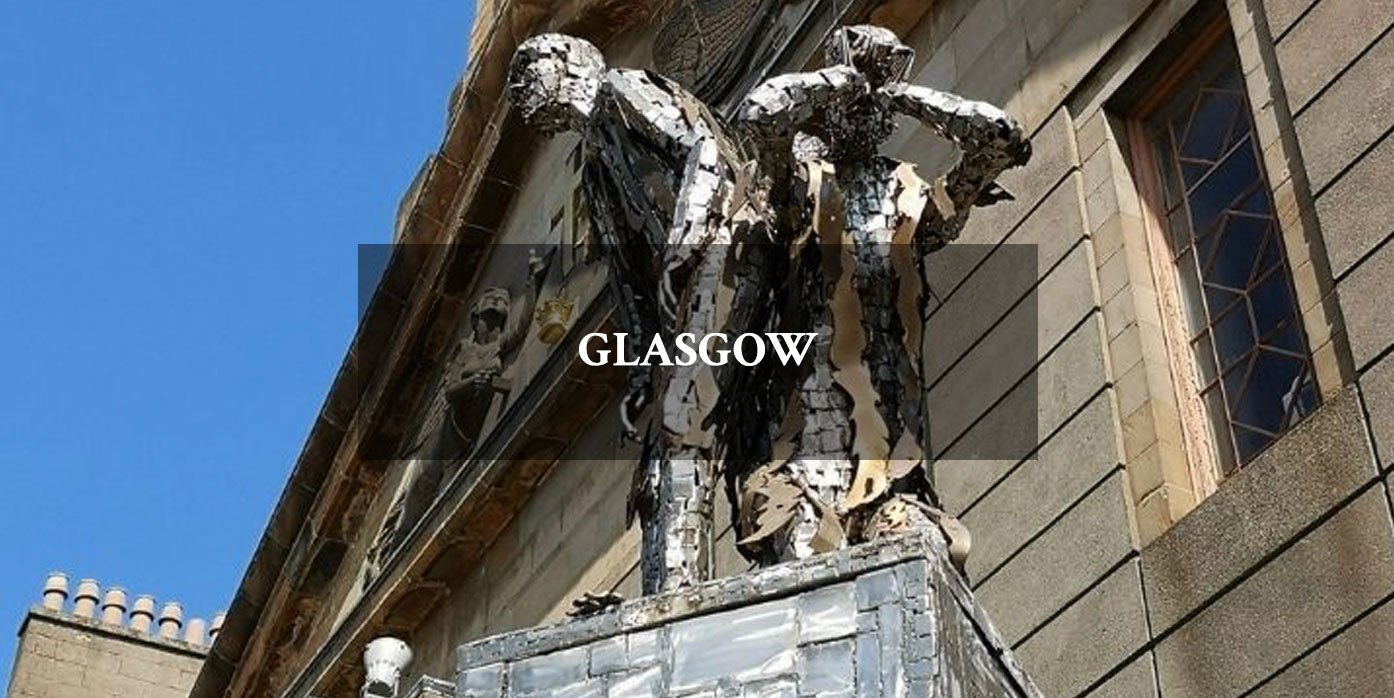

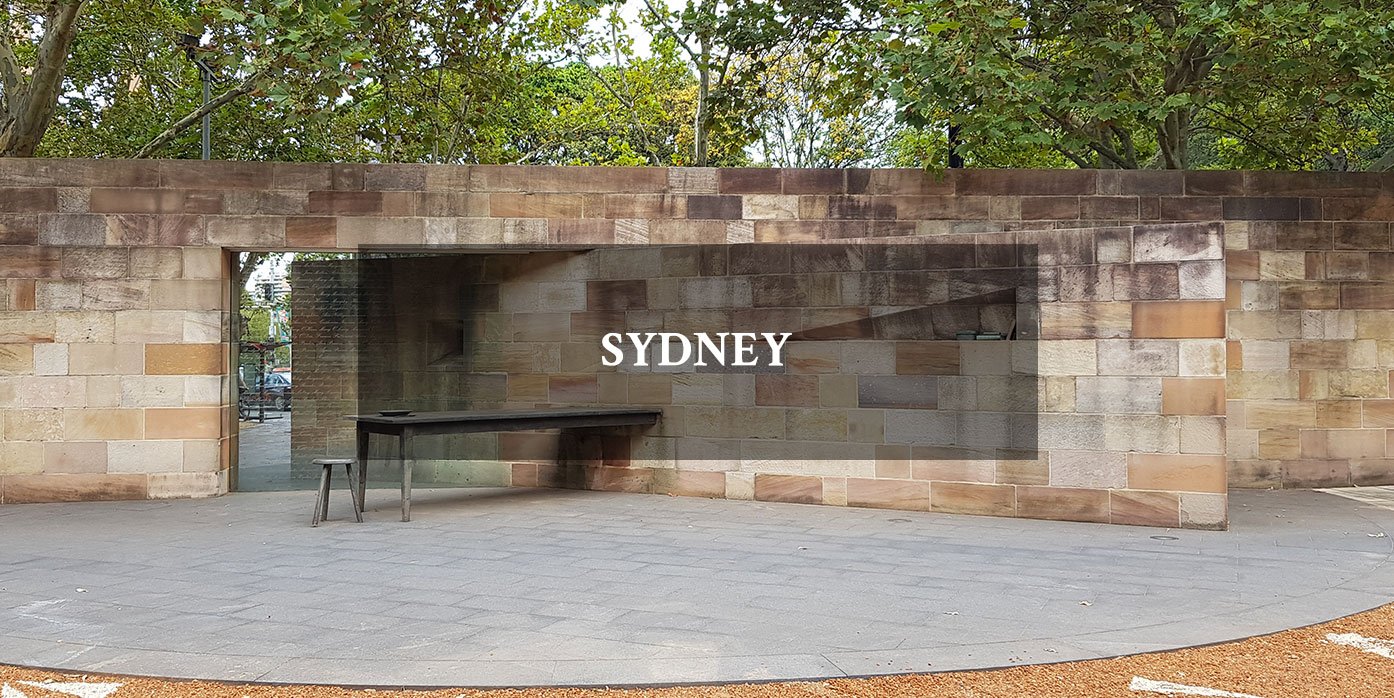

An Gorta Mór Memorials

Memorials to the Irish Famine exist in Dublin, in Ireland and throughout the world where the Irish Diaspora exist.

Unfortunately Manchester has not yet provided a permanent memorial.