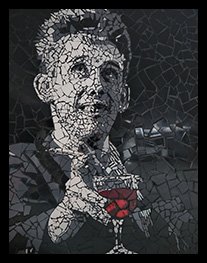

Shane MacGowan

Shane MacGowan (born 1957) was an Irish musician and songwriter, best known as the frontman and primary songwriter for the iconic Celtic punk band The Pogues.

Born in Kent, England, to Irish parents, MacGowan's upbringing deeply influenced his musical style and lyrical themes. With The Pogues, he revolutionized the punk genre by infusing it with traditional Irish folk music, creating a distinct sound that resonated with audiences worldwide. MacGowan's raw, poetic lyrics and gravelly vocals became synonymous with the band's rebellious spirit.

Despite his well-documented struggles with substance abuse, his musical legacy endures, cementing him as a seminal figure in alternative rock, giving visibility to the second-generation Irish in England, a previously uncharted facet of migrant life.

Early Brilliance, foreshadowing & Punk

MacGowan was noted for his precocious interest in literature; by age 11, he was reading authors including Fyodor Dostoevsky and James Joyce, and at 13 he was among the winners of a literary contest sponsored by the Daily Mirror.

He attended Holmewood House preparatory school and won a literature scholarship to Westminster School in 1971, but was expelled from the latter for possessing drugs in his second year. Between the ages 17 and 18, he spent six months in psychiatric care at Bethlem Royal Hospital in London due to his drug and alcohol abuse.

As a teenager he considered joining the priesthood – but then he found punk. “I was happy during punk. Incredibly happy,” MacGowan told Vox. “You call it chaos. I don’t regard it as chaos. I regard it as natural living.”

Briefly enrolled at St Martin's School of Art, he worked at the Rocks Off record shop in central London, and started a punk fanzine, Bondage, under the pseudonym Shane O'Hooligan, giving the Jam their first review. He then made the cover of Sounds magazine, with the headline "Cannibalism at Clash Gig", when JaneCrockford, bassist from the Modettes famously bit off his ear. His ear was actually still in situ but the cover had him sprawled over collapsing tables like a crucified bat, blood oozing from his lobe.

Shortly after this, he and bassist Shanne Bradley formed the punk band the Nipple Erectors (later known as 'The Nips') playing their first gig at the Roxy in 1977. Over three heady years they spat, spewed and crooned an eclectic mix of punk, 60s garage and pop, producing four singles in all. Shane and Shanne were the mainstays of the band, ripping through an impressive cast of characters including drummers Jon Moss (later Culture Club) and John Hasler (ex-Madness) and by the time big fan, Paul Weller, produced their last single ‘Happy Song’ in 1980, James Fearnley (to become accordionist with the Pogues) had joined the line-up as guitarist. Openers for The Clash and The Jam and they released a live album, ‘Only the End of the Beginning’ on their break up.

Shane was working at Stan Brennana’s Rocks Off record store, living on a staple diet of fried egg (lots of pepper) sandwiches on brown bread. Restless musically, he was sniffing around for something new and felt a hankering to get back to his roots. His mate, Spider, was playing with ‘The Millwall Chainsaws’ and it was this group, with the addition of friend, Jem Finer (banjo), that was to lose some bodies, gain some bodies and morph into ‘The New Republicans’ in turn morphing into the fragile early line-up of the Pogues then known as Pogue Mahone.

Their first gig was on 4th Oct. 1982 at the Pindar of Wakefield where Shane worked collecting glasses and booking bands and their early rehearsals ramshackle affairs in the Kings X flat of their friend, a pioneer in snakeskin earrings, who kept his stash in Shane’s bath. Memories of this time are dotted by the crashing, banging and chaos of those first rehearsals in the tiny, cramped back-room and marching with an animated Shane from Rocks Off Records up the road to the Black Horse pub where meetings on strategy for world domination with band champion Stan Brennan, Spider and crew would inevitably be interrupted by a spew of opposing views from Shane and Spider as they spluttered, ranted, raved, sniggered and sent beer glasses jumping from thumped tables while they fiercely debated anything ranging from Russian or Chinese politics to the exact geographical position of Vietnam. Just enjoying the first tastings of success, Boy George, in full regalia, used to frequent the pub and Shane and co. would take a break to sneer and snort as he snorted derisively back.

From the underbelly of London, the Pogues rose like a flame.

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan was born on Christmas Day 1957, in Pembury near Tunbridge Wells. His parents were Irish immigrants residing in Kent who moved around the south-east of England. MacGowan spent his early childhood in Tipperary, Ireland. He moved back to England with his family at age six and a half. His whole family was musical: MacGowan said he learned a song a day from family on his mother’s side and gave his first performance aged three. “They put me up on the kitchen table to sing and the song went down very well,” he told the Guardian. “I did public performances regularly after that.”

He began drinking as a child when his family gave him Guinness to help him sleep and suffered from the effects of drug and alcohol abuse, but argued in 1990: “Self-abuse, or whatever you wanna call it, is also incredibly creative.”

Then known as Shane O’Hooligan, MacGowan formed his own punk band, the Nipple Erectors – later the Nips – and made a demo for Polydor produced by Paul Weller. MacGowan and late-joining Nips member John Hasler, formerly of Madness, would break away from the fracturing group in the early 80s to come together with members of the Millwall Chainsaws to form Pogue Mahone – a corruption of the Gaelic póg mo thóin, or “kiss my arse”. They changed their name to the Pogues partly as a result of BBC censorship and gained a reputation for fierce live performances.

MacGowan guessed that the “timeless” quality of their music was at the root of their appeal. “You don’t have to be part of the youth subculture to relate to it – it doesn’t have teen angst or anything so fuckin’ stupid,” he told the NME in 1983. “It’s based on strong melodies, which to me is what a song is.”

The band drew rave reviews for their debut album, 1984’s Red Roses for Me, but the group struggled to capitalise on its success owing to its highly combustible lineup – which sometimes saw the Clash’s Joe Strummer fill the absent MacGowan’s shoes. They released two more classic albums in 1985’s Rum Sodomy & the Lash, produced by Elvis Costello, and 1988’s If I Should Fall From Grace With God.

MacGowan sought to bring the power of Irish folk music to the rock scene, with his writing drawing from literature, mythology and the Bible. “It became obvious that everything that could be done with a standard rock format had been done, usually quite badly,” he told the NME in 1983 as the Pogues were getting off the ground. “We just wanted to shove music that had roots, and is just generally stronger and has more real anger and emotion, down the throats of a completely pap-orientated pop audience.”

He frequently wrote about Irish culture and nationalism and the experiences of the Irish diaspora, reclaiming the racist “Paddy” stereotype. Early in his career, he often performed in a union jack suit – but in Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary, Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan, he said: “I was ashamed I didn’t have the guts to join the IRA – and the Pogues was my way of overcoming that.”

His dedication to his craft earned him the Ivor Novello songwriting inspiration award in 2018, following five albums with the Pogues and various solo releases. The Pogues’ highest-charting song, Fairytale of New York, a duet with Kirsty MacColl, reached No 2 in 1987 and became a Christmas classic.

Hell’s Ditch, released in 1990, was the band’s fifth album and the last to feature MacGowan as a member. After collapsing en route to support Bob Dylan in 1988, he was diagnosed with hepatitis and told he would die if he did not stop drinking spirits. MacGowan was ultimately fired from the band in 1991 after failing to turn up for live shows during a tour of Japan.

“By the end of it, I hated every second of it,” he told the Telegraph in 1997. “They’d moved so far away from what we were doing in the first place. I didn’t like what we were playing any more. I refused to knuckle under and become professional.” MacGowan moved from Thailand to Tipperary and formed the band Shane MacGowan and the Popes, who recorded two studio albums. He would rejoin a full Pogues reunion in 2001, which lasted until 2014.

In 2000, Sinéad O’Connor reported MacGowan to the police for heroin possession, hoping to discourage him from using. Despite his initial fury, MacGowan later expressed gratitude to O’Connor for helping him get off the drug. When O’Connor’s 17-year-old son Shane died in January 2022, MacGowan paid tribute to her, saying: “You have always tried to heal and help.” Following O’Connor’s death in July, Clarke posted the couple’s thanks for “your love and your friendship and your compassion and your humour and your incredible music”.

He had used a wheelchair since 2015, following a fall that fractured his pelvis, and subsequent falls that damaged his knees.

MacGowan’s last album was the Popes’ The Crock of Gold in 1997, although since 2015 he had been working on an as yet unreleased album of covers and originals with the Irish band Cronin. Among his final artistic output was The Eternal Buzz and the Crock of Gold, a lavish art book which was praised by critic Waldemar Januszczak for MacGowan’s “demented, wild, fascinating, scabrous kind of energy”. Copies of the book were sold for £1,000 each to raise money for MacGowan’s care.

MacGowan received a Lifetime Achievement Award from President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, in the National Concert Hall, Dublin, on 15 January 2018.

In December 2022, MacGowan was hospitalised with viral encephalitis, and as a result spent several months of 2023 in intensive care. On 30 November 2023, after receiving last rites, MacGowan died from pneumonia at his home in Dublin with his wife, Victoria Clarke, by his side.

Irish president Michael Higgins was among those paying tribute, writing: “His words have connected Irish people all over the globe to their culture and history … The genius of Shane’s contribution includes the fact that his songs capture within them, as Shane would put it, the measure of our dreams – of so many worlds, and particularly those of love, of the emigrant experience and of facing the challenges of that experience with authenticity and courage, and of living and seeing the sides of life that so many turn away from.”

Musicians paying tribute included Mercury prize-nominated Irish folk group Lankum, who called him “a titan”, while folk-rock singer-songwriter Frank Turner called him “one of the all time greats”. The Charlatans’ Tim Burgess called him a “lyrical genius” responsible for “some of the most exhilarating shows I’ve ever witnessed” and Fontaines DC and The Mary Wallopers have acknowledged his genius inspiration.

Billy Bragg was among the musicians voicing admiration for MacGowan’s craft, calling him “one of the greatest songwriters of my generation … the Pogues reinvigorated folk music in the early 80s and his songs put the focus onto lyric writing, opening doors for the likes of myself and others.”

During a concert in Dublin in 2022, Bob Dylan paused between songs to pay tribute to another singer-songwriter who was in attendance that night. “I want to say hello to Shane MacGowan”, said Dylan, praising MacGowan as one of his “favourite artists”.

MacGowan came to prominence in the 1980s as the singer and songwriter for The Pogues. In that role, MacGowan became, as the BBC Four documentary The Great Hunger: the Life and Songs of Shane MacGowan explained, “the first voice that arose from within the London-Irish to give defiant and poetic expression to a community which had never really felt able to proclaim itself”.

The Pogues gave visibility to the second-generation Irish in England, a facet of migrant life that had previously gone uncharted in mainstream popular culture.

MacGowan was not only pioneering in his evocation of Ireland’s diaspora in England – he composed songs of exceptional quality, attracting enormous critical respect and significant commercial success.

If, as seems likely, Shane MacGowan’s songs are sung for centuries to come, then we’d do well to recall their origins in – and echoes of – Ireland’s often overlooked diaspora in England.